Trilleen’s log: 13 September 2022

After many days wind bound in Kinsale waiting for the passage of a fairly horrible depression, during which I was royally looked after by Kinsale Yacht Club and got to participate in one of their excellent Sailability activity days – I ventured out round the corner and turned towards the north away from the south coast of Ireland

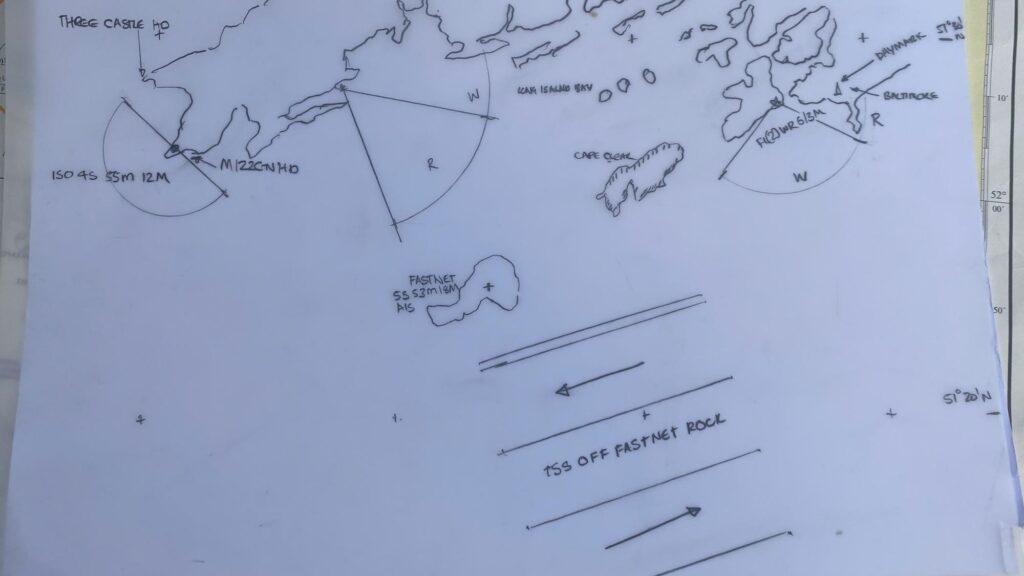

The passage from Kinsale to Bantry Bay, is a tour of some of the most famous lighthouses and marks of the seafaring world. From the Old Head Of Kinsale, a traditional fix for ocean liners departing to the americas, which was made by submarine torpedo the mass grave for RMS LUSITANIA’s company and passengers. Then onlwards to the Fastnet light, the turning mark for the yacht race that turned into a disaster in 1979 when a severe depression hit the race fleet. Trilleen was just abeam the Fastnet light when in a momentary flash of cell signal, the news of death of the Queen Elizabeth the Second, reached me, making for a sombre start to the night hours as I affixed a mourning band to the ensign and lowered it to half mast.

The passage from the Fastnet to Bantry Bay was a long slow struggle to windward through the darkness. The south west leg of each tack pointed Trilleen out into the vastness of the Atlantic. She doesn’t have the deep hydrofoil keels or tweaky rigs of modern performance boats, and she makes slow progress, rolling and head butting her way through the swells.

It’s very obvious that though Trilleen excels in coastal work and her low draft is an asset in finding an anchorage, she would much rather be given her head and let stand off on a tack for a week at a time, munching up the miles at little more than walking pace. She has a quiet competence about the way she deals with the sea, and gives great confidence that if asked a fortnight of the same wouldn’t be a problem. How her human would cope might be an entirely different question.

Approaching the entrance to Bantry Bay, I crossed tacks with the Sailing Vessel An Chobodan (The Sandpiper) drifting in from the Atlantic in the unveiling dawn towards the forty five mile wide basket of lights between Dursey Island and the Fastnet Rock, welcoming her with the assurance of a landfall safely made after 17 days at sea out of Canada. They called Trilleen on the ship to ship radio, curious perhaps, as to what such a tiny yacht was doing smashing upwind round Ireland. Ritual greetings extended we slid apart with mathematical inevitability.

My dawn was rewarded with a scribble of terns, lifting out of the sea’s deep shadow into the haloed yellow of a cloud filled dawn. Behind them the mountains of Ireland’s South West coast and the vast arms of Bantry bay opened up, followed a few hours later by a tiny anchorage in Dunboy Bay outside Castletownbere. Safe access to anchorages like this inevitably involve lining up a ‘tree’ with the ‘doorway’ of the ‘castle’. This naturally tends to provoke the questions: which tree and which doorway?

After drawing breath for a few hours I moved to Lawrence Cove Marina, where diesel legal for use in pleasure craft is available on the the pontoon. This isn’t the norm in the Republic of Ireland at the moment and when dealing, as I do with disability, it’s worth a diversion to find sites where a top up is possible. Rachel who runs the marina there was most kind and helpful, finding a place for Trilleen, refuelling her, sourcing a spare extra fuel container, and being altogether interested in the work of the Andrew Cassell Foundation, and indeed Sailing Trilleen’s trip.

That night in Lawrence Cove was welcome but the wind had news for me, and for once it was good. A South Easterly wind was due to come in at the dawn, filling and building through the day, before dying twenty four hours later. I was indecisive, and incited to action by consultation with Matt Grier at the the Andrew Cassell Foundation, and rapidly restored Trilleen to the sea state, before crashing out for a few hours.

Trilleen had, as I put it by text, ‘departed for points North. Riding the wind for as long as the SE flow lasts’. The opening part of the run from the light on The Bull and Calf, islands off the north Coast of Bantry Bay up towards the Skeligs of early Christian, and lately Star Wars fame, would be a dead run. That meant flying the mainsail and jib on opposite sides of the boat to make the best of the wind

The way you handle these depends on the sort of sailboat rig you have but in a cutter the only real option available (other than some exotic sail) is to fly the jib on one side and the main on the other: what the Americans call ‘wing on wing’ and we usually call being ‘goose winged. To prevent the jib collapsing with every roll of the boat a pole needs rigging and the main needs a preventer rigged to stop it smashing back across the boat if the self steering loses control. I’m slightly ashamed to say that because of the Hydrovane fit delays this wasn’t something I had practiced. However I got it all rigged, and it will be better rigged next time…

My uncertainty about Trilleen’s safety under these conditions led to a long evening babysitting the rig as we worked out way north, which coupled with some accumulated sleep loss from the previous passage wasn’t terribly welcome. As the night drew down Trilleen pointed closer and closer to the wind, on an increasingly fine reach pointing up towards the edge of Galway Bay.

Somewhere along the way, Trilleen’s plotter developed a fault. I’ve found the plotter is an important complement to the paper plot that, being old fashioned, I still maintain. I had to whip it out of the cockpit, and jury rig it up inside the cabin, and then seal the hole in the bulkhead with some of the damage control timber and sealant kept for such purposes. Even as I stuck it on I was dreading getting it off again. But watertight integrity matters and there is always a way.

Just past the mouth of the Shannon River, Trilleen fell into a hole in the wind, which was occupied by one of the most intense rain storms I’ve had the misfortune to experience. Rapidly struggling into a drysuit, I was incredibly grateful to Colin, shipwright, friend and contractor without whose loving work on Trilleen’s windows and hatch has left her a tight dry boat. As the rain continued I fretted about the the loss of speed, and continuously revised where we were likely to have got to when the wind deleted itself. It looked like the Aran Islands (Beware there are several of these) was still just possible so I elected to stand on.

The wind did indeed moderate throughout the night leaving me with a pleasant zephyr, then nothing. Unfortunately, the wind swung in the opposite direction to that which was forecast, so it was becoming progressively more difficult to reach the Aran Islands, and the only other possible port Roundstone, was so far away that the strong northerly wind which was about to rise would have scuppered my plans. So about 12 miles out from Inishmore I was forced to supply a little diesel assistance to the sails, and by the time I passed the light on the South West corner of the Aran Islands the wind vanished completely.

Dusk found Trilleen tucked away in a corner of Kilkieran Bay, sharing an anchorage with several thousand farmed salmon, and a gorgeous sleep.

Loving your writing Ian. Looking forward to the next episode. Douglas

Dear Ian

Many thanks for your very interesting and well written progress report.

Kinsale is one of my favourite places to spend time, not only for the sailing but also for the generosity and friendliness shown by the locals.

I will send you a copy of my Fastnet report.. I survived the 1979 race.

Good luck. I will call you in the near future.

Sounds like very hard work, but that you’re enjoying the challenge!

Going round into the Atlantic is exciting Ian. Thanks for the blog